Tackling the Gender Pay Gap: 5 Causes of Pay Inequality

Overlooked for promotions, bypassed for training and development, misunderstood, excluded and discriminated against – being a woman in the workplace comes with unique challenges and obstacles that many men do ...

Overlooked for promotions, bypassed for training and development, misunderstood, excluded and discriminated against – being a woman in the workplace comes with unique challenges and obstacles that many men do not have to contend with.

In both Australia and New Zealand, the gender pay gap is incrementally getting smaller. But progress has been slow and there is a long way to go before it’s closed. In fact, data shows that it will take 26 years to close the gender pay gap in Australia if progress continues at the current pace. That’s why earlier this year, the Australian government introduced the Workplace Gender Equality Amendment (Closing the Gender Pay Gap) Bill 2023 with new measures requiring organisations to take action.

What’s the current gender pay gap?

According to Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data, the national gender pay gap in Australia is 13.3%. The national gender pay gap in New Zealand sits at 9.2%. However, it has remained around the same level since 2017.

Misconceptions about the gender pay gap

Critics who do not believe in the validity of the gender pay gap often argue that the gap is driven by voluntary choices. One common misconception is that women’s salaries are reflective of their education, training and skill level.

This is despite the fact that data from the ABS shows that in 2022, 6.1 million women across the country held a non-school qualification, compared to 5.9 million men.

This data also showed that men who held a bachelor-level qualification were much more likely to hold full-time work (73.5% full-time, 11.4% part-time) than women with the same level of qualification (53% full-time, 26.1% part-time).

As the data shows, the argument that women fail to earn high salaries compared to their male counterparts due to a lack of education falls apart very quickly.

The fact is, many different factors contribute to the gender pay gap. Often, the reasons behind an organisation’s gender pay disparity are complex and ingrained. However, this does not mean that these problems cannot be solved and the gap cannot be closed.

Five key factors contributing to the gender pay gap

We’ve put together a list of five factors that contribute to the gender pay gap and the complex issues behind them. This is not a comprehensive list, but a brief overview that aims to help people get a better understanding of this wide-reaching issue.

1. Occupational segregation

Women in lower-paying industries and occupations

For the past twenty years, gendered occupational segregation has remained persistent in Australia. Female-dominated industries are typically lower paid than male-dominated industries. This is not because women choose to work in lower-paid jobs (which is a common argument made by critics of the gender pay gap), but because so-called women’s work is devalued and therefore workers in these industries are paid less.

A US-based 2009 study that tracked census data from 1950 to 2000 found that when women enter a particular industry, wages drop. This is backed up by other studies which have also found that when a higher percentage of females than males occupy an industry, it leads to lower wages within that industry.

Segregation within occupations and women in lower-paid roles

Segregation doesn’t just exist in male-dominated industries; it also exists within female-dominated occupations, such as healthcare or education. WGEA data shows that men hold the majority of leadership roles across all sectors in Australia, even within female-dominated industries. Only 19.4% of CEOs are women, and only 32.5% of key management positions are held by women. As the data from the ABS proves, a lack of opportunity for women in senior roles has nothing to do with a lack of education. Instead, these figures point towards discrimination, bias and a lack of opportunity.

Limited access to high-paying, male-dominated sectors

There are other complicated reasons why women have limited access to high-paying, male-dominated sectors such as mining, construction and STEM. There are additional obstacles that exist for women struggling to access these fields, such as discrimination, harassment, exclusionary cultures and gendered stereotypes about the type of person who is better suited to these roles. There are also physical barriers, such as design gender bias, that may prevent women from joining these industries – including a lack of female facilities, or equipment that has been designed by men for men.

Mining in particular is an industry that demands long hours and remote, site-based work that may not offer a great deal of flexibility. This lack of flexibility is incompatible with the demands of raising a family – of which the majority of unpaid domestic and care work falls to women.

2. Unconscious bias and discrimination

Discrimination in negotiating pay and benefits

Some of the data collected on negotiating for salary and pay rises over the years is slightly conflicting. For example, past studies have predominantly shown that women do not ask for pay rises as often as men. One of the most frequently cited studies was published in Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever’s 2007 book, Women Don’t Ask, and states that only 7% of women will negotiate their salary when applying for a new job as opposed to 57% of men; and less than one in five women will ask for a pay rise.

On the flip side, a more recent study of Australian women found that female workers were just as likely to ask for a pay rise as their male colleagues – but they were less likely to receive one.

Stereotypes and biases influencing hiring, promotions and pay decisions

Data collected by the WGEA proves that gender biases exist in nearly all employment decisions. The study showed that stereotypical beliefs often held women back from development opportunities and senior leadership roles, despite the fact that women and men do not have materially different aspirations for senior leadership positions.

The research also found that stereotypical beliefs still exist, with women being perceived to have less career motivation than men. These outdated beliefs can quickly limit a person’s exposure to career development opportunities.

Furthermore, the data also showed that women faced more obstacles than men during the recruitment stage of a new job. Gender-coded wording in job advertisements helped to reinforce stereotypes about which genders are better suited to particular jobs, potentially dissuading women from even applying. It also found that women were more likely to face tougher evaluation standards during the recruitment process, and were penalised for demonstrating competitiveness, self-confidence and ambition in job interviews.

Differential treatment and expectations based on gender

Microaggressions, differential treatment and systematic discrimination are some of the ways that gender bias manifests itself in the workplace.

Pregnant women and women who have recently returned to work from parental leave often face high levels of discrimination based on their situations, too, with one in two mothers indicating that they have experienced discrimination at work. And one in five mothers reported that they were either dismissed, made redundant, had their role restructured or did not have their contract renewed either during their pregnancy, when they requested or took parental leave, or when they returned to work.

The gender equality challenges faced by women of colour are compounded by racism, and the unique issues they face are often overlooked. In a report by the Diversity Council of Australia that surveyed culturally and racially marginalised (CARM) women, it was found that:

- 75% of respondents said that others had assumed they worked in a lower-status job than they did and treated them as such.

- 61% reported experiencing racism at work in the past two years, and 48% said they had experienced sexism at work over that same period.

- 85% felt they had to work twice as hard as employees who weren’t CARM women to receive the same treatment.

- 77% of those surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that decisions about hiring and promotions are made through informal networks, which they struggled to access.

3. Work-life balance and caregiving responsibilities

The disproportionate burden of caregiving placed on women

We can’t talk about the gender pay gap without also covering the fact that within hetero-normative households, women are the ones who take on the majority of domestic and care work.

Gender equality statistics released by the Australian Federal Government in December 2021 showed that 54% of families reported the main person looking after children was a woman. In contrast, only 4% of families reported that a man usually or always looked after children. The remaining 40% of households claimed the responsibility was shared equally.

These numbers are driven by social and economic structures that reflect and reinforce gendered stereotypes. And because the burden of domestic and care work almost always falls on women, the flow-on effects and consequences disproportionately affect women.

Career interruptions and reduced work hours impacting earnings

According to the Australian Government’s gender equality statistics, working mothers experience a significant financial setback due to reduced working hours and time out of the workforce. The result is that women’s earnings are reduced by an average of 55% in the first five years of parenthood.

In addition to this, research by the Grattan Institute estimated that an average 25-year-old woman with children will earn approximately $2 million less over her lifetime compared to the average 25-year-old man with children. The report definitively stated that increasing paid hours for women would be the single biggest change that could help close the gap in lifetime earnings between women and men. But while stereotypes and other barriers exist, the gap will persist.

In saying all this, we cannot ignore the fact that while women are the ones who are financially penalised for having children, gendered norms also deprive fathers of the chance to spend more time with their children, particularly in the first year of their child’s life. By placing the responsibility of the primary caregiver on the female member of the household, both parties are losing out in one way or another.

Access to flexible work arrangements and parental leave

Flexible working conditions are a big benefit for both parents, as it means that caring responsibilities can be more equally shared. Having equal access to parental leave after the birth or adoption of a child will also have a big impact on closing the gender pay gap for women.

According to data collected between 2020-21 by WGEA, 60% of employers offer access to paid parental leave (either to both women and men or to women only) as well as the government scheme. However, women account for 88% of all primary carer’s leave utilised and men account for only 12%.

The availability of paid parental leave for both parents means a much more equitable division of unpaid care and paid work, which helps to promote a healthy family work-life balance. By promoting equal paid parental leave, one parent may not feel it’s their sole responsibility to take a significant career break over the other.

4 . Education and training

Gender disparities in educational choices and fields of study

In 2022, a total of 442,000 people were studying a science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) field. But only 27% of STEM students were women.

Women are not choosing to avoid STEM topics because they’re unattracted to these subjects. It’s because of the challenges they face when trying to enter this field, which often start at a very young age.

Due to deeply-rooted stereotypes and biases, studies have shown that both family members and educators may steer girls away from pursuing STEM subjects and, ultimately, following a career in those fields. Even if they do study a STEM qualification, women then need to overcome various other challenges that exist within male-dominated industries – such as a lack of female role models and mentors, exclusionary culture, the increased risk of sexual harassment and gender bias.

The statistics of women in STEM in New Zealand are a little bit more uplifting – with 48% of STEM jobs held by women. However, senior leadership roles in these sectors are still predominantly held by men.

Lower representation of women in higher-paying professions

A low representation of women in higher-paying industries, such as STEM, is a direct contributor to the gender pay gap.

With less women studying STEM topics, there are naturally fewer women who work in these fields. Traditionally, it’s these male-dominated areas that can offer the highest-paying roles – however, it should be noted that the gender pay gap within STEM in Australia is about 18%, or $26,784.

The Grattan Institute has discovered some concerning statistics when it comes to gender equality in fields of study. Its research found that if trends keep progressing at the current rate, gender equality will not be achieved in engineering for more than 150 years.

Limited access to training and professional development opportunities

The fact that women have less access to training and development in the workplace goes hand in hand with data that shows women are often less likely to ask for a pay rise (and less likely than men to get one even if they do ask).

Often, women are not aware that these opportunities exist, as information is deliberately withheld from them or they are simply overlooked. Another contributing factor is that they are less likely to put themselves forward for opportunities because of a lack of self-belief in their own abilities and deservedness.

With limited access to learning and development, women automatically have less chance of being promoted and are less likely to progress further up the career ladder.

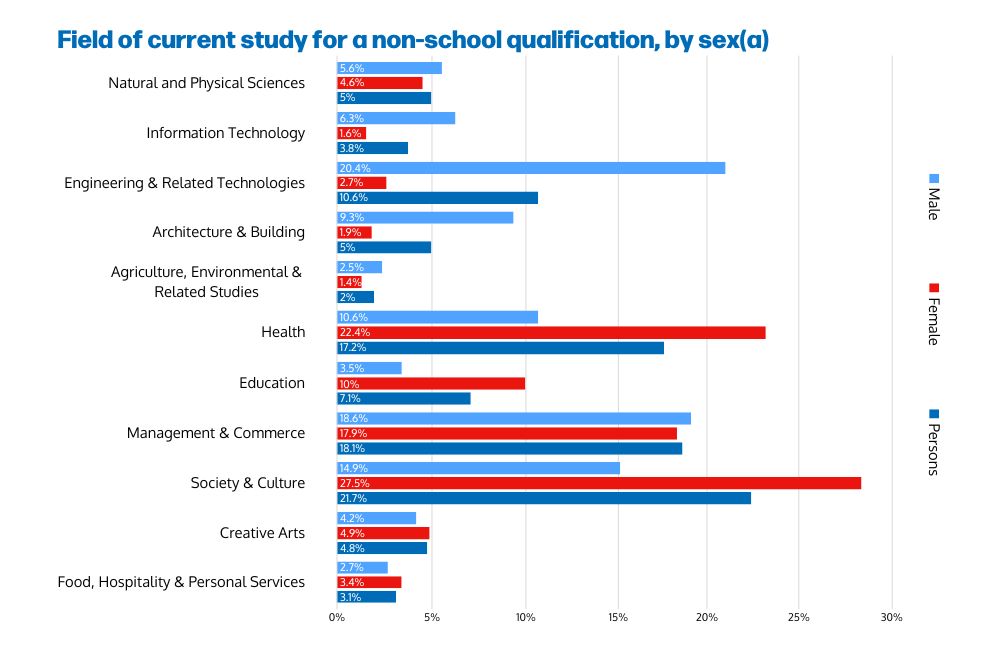

According to the ABS, 2.1 million people were studying for a non-school qualification in 2022. One of the biggest gender disparities was in engineering & related technologies. 10.6% of all students enrolled (persons) were in this field, with 20.4% male students and 2.7% female students.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Education and Work, Australia, 2022, Table 5

5. Underrepresentation in leadership positions

Limited opportunities for women in senior roles

LeanIn.Org is a US-based organisation focused on empowering women around the world. Each year, they release a comprehensive report called the Women in the Workplace Report. Their latest report has found that, although women are still underrepresented in leadership roles in the US (36% of senior management or director roles are held by women), female leaders have begun switching jobs at a noticeably high rate. Furthermore, 48% of female leaders who switched jobs in the last two years did so because they wanted more opportunities to advance.

Compared to men in similar leadership roles, women do more work to support employee wellbeing and promote diversity, equity and inclusion – but are rarely recognised for it. They feel burned out and unappreciated and are looking to move on.

Fewer women in positions with decision-making power and higher salaries

Data collated by the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre and WGEA sends a very clear message to organisations that have a lack of female leaders: your bottom line is going to suffer.

The research proved that increasing the representation of women across key leadership roles led to increased productivity, greater profitability and overall better company performance. In fact, more women in leadership positions added market value of between $52m and $70m per year for an average-sized organisation.

Despite this evidence, women occupy only 32.5% of key management positions in Australia.

Lack of role models and mentorship for career advancement

It’s incredibly important that more women are given the opportunity to progress into leadership roles. The fewer women in managerial positions, the easier it is for harmful stereotypes to exist. This further exacerbates gender pay inequality and also has a wider effect on societal and cultural gender biases, especially for CARM women

It also means that there are fewer women in senior roles that female colleagues can look to for guidance, career advice and mentorship.

On top of this, gendered violence has a significant role to play when it comes to women’s career progression and the gender pay gap. For example, the disrespect and outright abuse that women face online can be a deterrent to using digital spaces to promote career and business interests.

Where to start

With so many obstacles in the way, it might seem like a gargantuan task to shrink the gender pay. But while there are many challenges to overcome, it is far from impossible to close the gap.

If your company has a gender pay gap and you’re looking for ways to close it, one of the first steps you can take is to complete a gender pay gap audit and use verified data to identify the areas where your company falls short. From here, you can begin working on a strategy to address the causes of your gender pay gap and take positive steps in the right direction.

About ELMO Software

ELMO Software is the most preferred HR, payroll & expense management software provider in Australia, compared to our competitors. And when people choose ELMO, they rarely think of switching. In fact, almost 70% of our customers say they’re unlikely to change their HRIS provider within the next 12 months. With a highly configurable product that can be tailored to suit your business, industry-leading security practises, and a supportive implementation process, it’s no wonder more people prefer – and stick with – ELMO.

Visit our website to learn more about ELMO’s product and how our software can help your business.

*YouGov findings are based on the survey responses from 347 HR decision makers in Australian businesses with 50+ employees. Responses were collected in March 2023.

HR Core

HR Core